Synthesis: Legal Reading, Reasoning and Writing in Canada [book notes]

- 2nd Edition

- Margaret E. McCallum

- Deborah A. Schmedemann

- Christina L. Kunz

Chapter 1

- The Lawyer's Roles

- Lawyers are advisors/advocates for their clients

- as an advocate the lawyer will, in court, defend their clients based on events of the past hoping to achieve the most fair outcome. The lawyer will also look forward in seeking the most favourable and fair outcomes for their clients

- Lawyers take life situations and frame them within legal constructs

- Process: fact investigation, research, reading the law, reasoning about the application of the law to the clients situation, writing out or orally presenting the analysis

- The skills of a lawyer are broad and encompass the skills of many other professions, ex, an "engineer's precision"

- Lawyers are also servants to the public

- Aids in the implementation of laws

- Lawyers actions in court are continuously developing Common Law

- Canadian Bar Association's Code of Professional Conduct

- The Legal System

- Local government are the creations of provincial/territorial governments and can only which they are allowed to do by their parent body

- The federal and provincial/territorial levels have three branches: legislature, judiciary, executive

- legislature makes the law

- judiciary: interperts, applies

- executive implements the law

- there is overlap between the three branches

- Aboriginals can form their own governments of sorts. Their powers of self government are a lot more broad than the powers that provincial or local governments receive.

- Rules of law exist in: cases, statues, regulations and court rules.

- Rules of law need to be predicatable

- Legal rules can be stated in an if/then format. "IF the required factual conditions exist," "THEN the specific legal consequences follow."

- factual conditions or legal consequence

- And If/Then/Unless statement can modify the If/Then situation to explain situations where the rule does not apply

- One could also say If and not some stuff Then...

- if a list uses the word "and" all elements must be fulfileld aka "conjunctive rule"

- if a list uses the word "or" at least one of the elements must be fulfilled aka "disjunctive rule"

- ex

- the person at rice, and

- the person ate

- a) an apple, or

- b) a pear, and

- the person drank water

- in the above example the person must have at rice, and either a banana or an apple, and drank water for the condition to occur.

- "And aggregate rule required you to determine whether enough of the suggested factors have been met to justify applying the legal consequences."

- that is, there will be a list of conditions that could apply, and "some" number of those conditions could be enough to trigger the legal rule

- "A balancing rule requires you to balance factors favouring either outcome in order to determine whether the legal consequences will apply."

- this could mean that there will a section that says something like, "if the harm of condition a outweighs the harm of condition b

- Aggregate and balancing rules include ambiguity which can be good or bad. It allows for flexibility but that flexibility brings along unpredictability with it.

- Plural consequences: there are multiple consequences, they are conjunctive, they use the word and, as a consequence someone might have to do this AND that.

- Alternative consequences: a consequence can be chosen from a set, the word "or" is used and is disjunctive. The person does this OR that.

- A consequence that is an ultimate practical condequence is one which directly states what the condequence is, for example, a fine

- Intermediate legal condequences might say that the consequence is an offence. One would then have to do further research to determine what is is meant by offence.

- Legal rules can be represented in charts, lists, paragraphs... one should choose the method which best depicts the rule

- administrative agencies include: boards, tribunals or commissions

- statues are used to create these, they also define their powers

- "If every statutory illegality, however trivial, in the course of performance of a contract, invalidated the agreement, the result would be an unjust and haphazard allocation of loss without regard to any rational principles." said Professor Waddams in the book, The Law of Contracts, 3rd ed. (1993) on page 381

- most cases enter the legal system at the trial court level

- some court systems force people to attempt to use alternative dispute resolution mechanisms before going to trial to attempt to resolve the issue

- A summary judgement is when a "judge decides the case based on written materials developed during discovery.."

- Appellate courts hear appeals

- "...appellate courts articulate and refine legal rules of broader application."

- "The lowest level of court in each jurisdiction is called the provincial or territorial court."

- some jurisdictions have family courts

- Superior courts are above the provincial and territorial courts

- administered by the provinces/territories

- judges appointed and paid by the federal government

- Depending where, the names: Court of Queen's (or King's) Bench, Superior Court, Supreme Court-Trial Division.

- above these in each jurisdiction is a single appellate division

- Describing the court system through text has become tiresome, here is an image taken from http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/dept-min/pub/ccs-ajc/img/Justice-chart-eng.gif which was found here http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/dept-min/pub/ccs-ajc/page3.html

- Federal courts deal with federal matters

- Jurisdiction involves geography but also in subject matter or types of cases

- Courts have defined jurisdictions

- need "personal jurisdiction over a party based on the party's contact with the jurisdiction (in the geographic sense of the word)"

- considerations: citizenship and the place where the events occurred

- needs jurisdiction over the subject matter

- Two broad categories of court jurisdiction is general and specific (ex family court)

- court opinions operate "as law under the doctrine of stare decisis"

- "Stare decisis et non quieta movere" means "to stand by precedents and not disturb settled points."

- this helps to provide consistency in the law, that current cases which are similar to cases in the past will be resolved in similar ways.

- it also makes the court system more efficient because it means that similar cases do not need as much examination as the original case

- Of course times change, and we would not always want to be stuck with earlier decisions, and in fact we are not. The attitudes change and evolve over time. This is of particular interest to me because of my interest in Information Technology Law and because it evolves so rapidly. Judges and lawyers can find ways to differentiate what are often two very similar cases in order to set a new precedent. Appeals courts can also overrule previous precedent in order to create dramatic change.

- courts are expected to rule similar to their past decicions

- courts are bound by decisions made by higher courts in the same court system

- judges are expected to make decisions "in accordance" with previous decisions made at the same level and in the same system but are not bound by them

- decisions that courts must adhere to are considered "binding" or "mandatory" precedent

- decisions which are not binding can still be persuasive

- The Supreme Court of Canada is able to overrule its previous decisions, though this was not always the case

- newer precedents can sometimes be considered to be more persuasive

- unanimous decisions are also weighted heavier

- even the quality/thoroughness of the decisions can play a role in determining its weight as precedent

- similarity also plays a role

- sometimes precedents from entirely different countries can be considered persuasive

- there unpublished decisions and often they are not considered to form a part of common law and given substantially less weight

- Reading a case

- cases have facts, including the dispute between the parties that has led to the case and matters of law or the response of the legal system

- like reading anything else: who, what, where, when, and why are important questions to be asking yourself

- it is good to know which courts are involved, previous decisions if you are reading an appeal, who were the judges or judge, when, what are the decisions and why were they made

- the outcome of the case will serve as precedent in the future and the ruling, or the outcome teaches us a lesson: what will happen if this fact scenario occurs again?

- Format of a case:

- Citation Information: on the first or second page at the top. It "identifies where the case is published."

- Case Name (aka style of cause): in italics, identifies parties. Common party designations in a civil lawsuit: plaintiff, defendant, appellant (person bringing forward the appeal) and the respondent ("the person opposing the appeal")

- plaintiff v. defendant, but sometimes reversed on appeals

- v. stands for versus but is read "and"

- non- adversarial proceedings begin with "Re" and user "and" instead of "v."

- Criminal cases are usually R. v. the person being charged. R. stands for Rex or Regina

- Court, Judges, and Date

- Publisher's Editorial Material: sometimes called "headnotes," a bunch of words or small sentences that are used as search items. These are not written by the court and cannot replace reading the actual case

- Court's Editorial Material: sometimes a synopsis of the case may be included, but the author may have not been the judge and does not serve as a substitute to the actual case

- Authorities Referred To: other materials that the case referred to, ex, other cases or even academic texts

- Procedural History: some of the history of the case, particularly if the case is an appeal

- Lawyers for the Parties: can be helpful in obtaining further information

- Authoring Judge: Immediately before the opinion. If there is more than one judge it will be let known which ones agreed and which did not

- Opinion(s): the organization can differ from judge to judge. Usually one or more of the following occur first: "the procedure in any lower court(s) before the case reached this court, the issue(s) raised by the case, and the outcome(s)." This is followed by the facts. Most of the opinion regards the legal issues raised and the resolution of the issues. The final paragraph will have the courts conclusion/decision.

- Remedy: often in italics

- To form a "majority opinion," the one that matters most, it must have more than half of the votes.

- If a judge agrees (concurs) with the majority opinion but wishes to add their own reasons they produce what is called a "minority opinion."

- If the judge disagrees with the result they form what is called a "minority opinion."

- Sometimes there is no majority opinion because of highly diverse views among the judges.

- "the opinion drawing the largest number of votes, although less than half, is called the 'plurality opinion' and generally is viewed as the most influential of the opinions."

- this book says that one will likely have to read the case a few times in order to fully understand it

- Briefing a Case

- "A case brief is a structured set of notes on a case."

- answer the questions of who what where when and why

- what events led up to the litigation

- what is the case history, is this an appeal? What happened at the first trial? who what where when why

- what did the court(s) rule, who ruled, why did they rule in that way? who one? who lost?

- Structure

- Heading: case name, court, date, citation of the case, the judges

- the reputation of judges can impact the weight given to the decision when determining precedent

- Procedural History: who sued who, past rulings if applicable (who won and how), if this is an appeal, who won, who brought the appeal, has the case been appealed again (what is going to happen in the future)?

- Parties: not just the people but the relationships involved, ex customer of a business

- Remedy Sought:

- Facts: who what where when why. But boil it down to what is necessary.What facts must you know to understand the case? What do you need to know to understand what the court was thinking? Do provide facts that provide context. An emphasis on the facts that are needed to understand the ruling, more so than the facts which create context.

- Issue(s): The question that the court answers. "Issue = (law + facts)"

- "Substantive legal rules govern the conduct of people in the real world..."

- "procedural rules govern the conduct of litigation, that is, events in the legal system"

- some issues may be more important than others

- Holding(s): "The holding is the court's answer to the issue." Connects law to facts. Multiple holdings if multiple issues. How the dispute concludes. Holdings come in varying degrees of generality.

- Rule(s) of Law: Facts that lead to an outcome makes up a rule of law. Courts use rules of law to make a decision. These can come from various places like precedent but can even be made new if it is a new situation. If there is a new rule being created the court might signal this by stating "We thus rule..."</li>

- Reasoning (aka Application): How the rules of law applied to the case. This may include items which were considered but ultimately dismissed. It should also include the judge's sources, these sources vary importance. Sometimes a case will pivot on a source, or merely use a source to slightly bolster reasoning.

- Optional Components

- Dictum/dicta: non-essential remarks. Not considered precedent that courts can be bound by. Though these can be persuasive. Only facts that were critical to the outcome of the case can become binding precedent. Extra stuff the court thought was useful to share but was not essential to the case. This might include hypotheticals, what would have happened if the the facts were slightly different.

- Concurring and Dissenting Opinions: state them

- Questions: questions that the court have left to be resolved in the future, or questions that remain after reading the case

- All in all, provide whatever information you need to understand the case in the brief.

- multiple cases, when considered together can inform you of rules of law which would have not been apparent by if they were considered individually. one may also detect patterns by observing the results of multiple cases. perhaps the law is becoming more liberal or perhaps it is becoming more conservative.

- appeal level decisions from other jurisdictions carries more weight than an trial level decision from another jurisdiction

- when categorizing for the purposing considering multiple cases it is important to note the court hierarchy and the chronology of the cases

- track the rules of law

- read -> brief -> determine the relationships between cases

- keep in mind if the cases are binding or merely pursuasive

- arranging the cases on an organized map, or in a graphic of sort could be useful

- or since I'm a computer nerd, perhaps one day I should develop some software to do this for me

- sometimes rules may appear different from case to case, it may indeed be that the rule is changing or that certain cases only dealt with certain aspects of the rule or perhaps the rule was simply re-phrased but means the same thing

- understand the similarities and differences of rules stated in various cases.

- categories to consider: "material that is identical in all rules, material that is similar in all rules, material that appears in only some rules, or material that differs from rule to rule."

- material which is identical in all rules can be summarized into a single statement which describes them all

- some cases that are similar can be merged into the above if they wont change the result, but if they do change the result you can modify the above with conditional statements such as "unless."

- you're trying to get some sort of take away message from all this combining, and this message should not contradict its parts

- EXAMPLE of combining cases

- lets say we are considering two fictional cases

- case a: person was driving 150km/h in a 100km/h zone. Gets caught, charged and convicted.

- case b: person was driving 150km/h in a 100km/h zone. person was on their way to a hospital because a passenger was in imminent danger. The person gets caught. Had the person not had the health emergency as a mitigating factor the person would have been charged and convicted.

- when combining these two cases you can create a rule

- IF one is driving above the speed limit, THEN one is liable to be charged UNLESS it is for reasons of medical emergency.

- or

- IF one is driving above the speed limit not for the purposes of a medical emergency, THEN one is liable to be charged.

- For the record I don't believe this is actually true, call 911 instead.

- But we can see that this rule can be applied to both cases, and using the rule get to the same result as actually occurred.

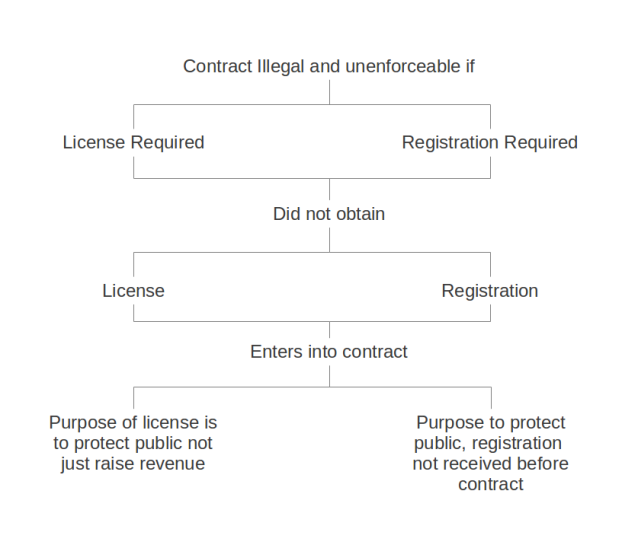

- It could also be used to describe something like this with a flow chart. From the text there was a fact scenario that resulted in a chart similar to this

Along the left was a case where a contract was deemed unenforceable because the person completing the work did not have a license to do the work, thus the work would have been illegal and the court didn't want to support illegal work notably in this instance because the license was important to ensuring public safety. Along the right some re-wording has occurred. As depicted it shows that a contract was invalid due to illegality because of the fact that a registration was not obtained. The plaintiff was not allowed to contract for work without the registration thus technically speaking making the contract illegal. The registration like the license just discussed also serves a purpose with regards to protecting the public. However, in the actual case, the plaintiff won and the contract was enforceable even though illegal because the plaintiff practically had registered at the time and in fact did obtain the registration. At the time of contracting it appears the registration was probably in some processing queue. I believe the registration actually was granted before the work was completed and this was important in overlooking the fact that the contract was technically illegal. We can see here that this flow chart has been worded in such a way that it allows the left and the right to share the same outcome, the shared outcome of an illegal and unenforceable contract. Though the registration was received before the work was completed, the diagram has phrased it if it had not. This allows us to see the commonality in the two cases that IF a party does not have the authority to contract, THEN the contract will not be enforceable UNLESS the authority is granted before the work is completed.

Along the left was a case where a contract was deemed unenforceable because the person completing the work did not have a license to do the work, thus the work would have been illegal and the court didn't want to support illegal work notably in this instance because the license was important to ensuring public safety. Along the right some re-wording has occurred. As depicted it shows that a contract was invalid due to illegality because of the fact that a registration was not obtained. The plaintiff was not allowed to contract for work without the registration thus technically speaking making the contract illegal. The registration like the license just discussed also serves a purpose with regards to protecting the public. However, in the actual case, the plaintiff won and the contract was enforceable even though illegal because the plaintiff practically had registered at the time and in fact did obtain the registration. At the time of contracting it appears the registration was probably in some processing queue. I believe the registration actually was granted before the work was completed and this was important in overlooking the fact that the contract was technically illegal. We can see here that this flow chart has been worded in such a way that it allows the left and the right to share the same outcome, the shared outcome of an illegal and unenforceable contract. Though the registration was received before the work was completed, the diagram has phrased it if it had not. This allows us to see the commonality in the two cases that IF a party does not have the authority to contract, THEN the contract will not be enforceable UNLESS the authority is granted before the work is completed. - The lesson to take away from this is that in finding commonalities between cases one can re-work the language to better depict the the situation.

- This could possibly be thought of as rearranging formulas to fit a template.

- 1 + 2 = 3

- 1 = 3 - 2

- we can see that the second equation is in fact the exact same as the first one if we were to rearrange it.

- describing the "features" of cases and comparing them could be of use to. The way that you can, on some websites, compare the features or specifications of electronics side by side in a grid form. Some features could include: "case name, court, and year ... real-world roles of the parties, the claim (also known as 'cause of action'), the relief sought (also known as 'remedy'), the salient facts, policies stated by the court and the holding(s) of each case on the issue(s) being examined."

- look for patterns that explain the holdings

- if cases are conflicted, be sure the consider the most important cases more, such as binding ones over persuasive ones, ones from higher courts than lower, more recent versus older etc.

- sometimes cases simply cannot be combined in the way described in this chapter

- was there a radical change in the mentality of the courts, were previous decisions overruled?

- are the facts radically different? the people involved radically different? the relationship between the plaintiff and the defendant radically different?

- sometimes cases will be an outlier. Maybe for some reason a judge is unusually sympathetic to someone's cause and that sympathy leads to rule in their favour, even though, they perhaps maybe should have not.

- or perhaps a case has some highly unusual characteristic

- The purpose of this chapter was to discover methods that will help one "generate a rule or pattern that encompasses the content of many cases"

- legislation contains rules

- statues must conform with the constitution

- "...regulations made pursuant to a statute [are] called subordinate legislation"

- there are other important rules that are formed as result of Aboriginal self-government agreements

- there are also other sources of rules

- legislative process

- changes to legislation can basically come from anyone as long as they can find a way to get a member of the legislature to turn it into a bill for debate

- federal parliament = bicameral legislature

- elected house

- appointed Senate

- usually bills begin in the House of Commons, the elected house, then are passed onto the Senate. They have to gain approval from both to become law

- bills often come from cabinet ministers.

- bills can originate with any member, but have very little chance of succeeding. These are called private member' bills.

- debated etc etc (not taking notes on this)

- Interestingly however the text says this: that instead of a true debate, "[m]ore often, debate entails a series of speeches by the bill's supporters that go unheard by most of the legislators."

- lobbyists must be registered

- when a bill becomes law it is called a statute/act

- actual enactment might be delayed, this might be due to regulations being made in order to implement the act

- judicial process is intended not to be political

- legislative process is highly political

- legislative intent is a bit of a fiction since even a single piece of legislation is formed by many people and it is unlikely that they all hold the exact same intent and interpretation. Nonetheless, legislative intent is still an important concept.

- it is important that when considering statutes that you are considering the appropriate statutes for the time frame being considered. This can become more complicated when the statue has been amended several times.

- standard components of a statute

- title and citation: sometimes given a short title too. The citation includes the year the statute was passed, and the chapter which was assigned to it in the published acts for that year. The word "the" is sometimes included in the title, sometimes it is not. Bills are given names like C-X where X is the nth bill introduced in the session. Senate bills are prefixed with S rather than C. And again as with bills, X represents the nth bill for the senate during the session. X between the Commons and the Senate have NO relation. Bills often have long names. Sometimes people will continue to call what has become and Act by its C-X name.

- preamble, purpose statement: Does not always exist. This is, as obvious by its name, the purpose, why the statute exists, what is it attempting to accomplish, what issues is it attempting to address, what are the desired results. When these descriptions exist in the preamble rather than in the act they are not officially part of the act, they are just there to guide the reader and provide inferences into the intent of the act.

- Definitions: clarify technical meanings, and to narrow the definition of words. There may be multiple sections of definitions for long acts. Words may even become redefined.

- Relationships to other statutes: Generally more recent acts will overrule older acts if there is overlap or conflict. This section can make how to deal with overlap/conflict explicit. It is possible to give ultimate authority to another act.

- Power to make regulations: statues often intend that regulations will be created in order to implement the statue. The regulations will likely be created by the body which will administrate the act. In other words, legislature might delegate power to another body to make regulations

- Effective date: when the legislation becomes active. Sometimes it is necessary to do further research to determine this date. Knowing this date is important before one relies on it. An additional reason why such a delay might occur is in order to have time to inform the public about the upcoming changes in the law.

- General Rule: what the statute encourages or prohibits. This is the main part of the statute. Often there are multiple rules.

- Exceptions:

- Consequences and Enforcement: some statues require you to look elsewhere for consequences and enforcement provisions.

- Briefing a statute

- condense, make it relevant to you and if you are reading it for specific purpose, make it relevant to that purpose

- IF... THEN... can also be useful here

- plain meaning vs. purpose approach

- resolving ambiguity: "case law, indications of the legislatrue's intent, canons of construction (maxims for reading the words chosen by the legislature), and the user of similar statues and persuasive precedent."

- vague statues may have resulted because legislators were unable to agree on precise wording

- among many other reasons of course

- purposive approach: figure out what the purpose of the statue is, what "evil" or "mischief" was being corrected? Then interpret the statue in a way that is in line with correcting the evil which needed correction.

- golden rule approach: read the statue plainly unless it results in an absurd/unconstitutional result.

- With respect to interpretation the Canadian Supreme Court says, "Today there is only one principle or approach, namely, the words of an Act are to be read in their entire context and in their grammatical and ordinary sense harmoniously with the scheme of the Act, the object of the Act, and the intention of Parliament." This is called the "modern approach."

- past cases provide guidance on interpretation

- courts: provide authoritative interpretation and assess constitutionality

- statutes can be declared unconstitutional in whole or in part

- "... if the court interprets a statue in a way that the legislature did not intend, the legislature can overturn the court's decision by amending the statute. The amendments will not change the outcome for the parties to the dispute that produced the objectionable interpretation, but they will change the rule for the future."

- legislative history plays a role in helping discern legislative intent. This could includd a recommendation made by a legislative comitee, the debates had as the bill was going through the process of becoming a statue. Different aspects are considered more authoritative than others. Formal documents will be weighted heavily, so has content from the sponsors of the bill.

- "In the end, and Act means what the court says that it means, not what a member of the legislature thinks that it means."

- The legal context will also be considered when interpreting statutes. Is the statute attempting to codify what already existed in common law? Is there a pattern to be seen from reviewing the history of amendments? How do other rules of law interact with the statute in question? Is one interpretation in conflict with another rule of law while another is not? It is probably the case that legislators were aware of the constitution and did not intent to be in conflict with it.

- There are rules in each jurisdiction that set out rules on how to interpret statutes. For example, sometimes the preamble of a statue is part of the statute, in some cases it is not.

- Sometimes policy issues that existed at the time of the creation of the statute can provide interpretation guidance

- Sometimes government bodies will produce interpretation guides, this might come in the form of an FAQ. If this were to happen there is a good chance that it would come from the administrating body. The Canadian Revenue Agency might create guides in order to help people with their taxes.

- imagining a fact scenario that, or a case, that would fall right into the hands of the statute can also aid in helping interpret a case. Often it is the case that legislators are responding to incidents which have actually occurred, is it possible to guess what such an incident may have been?

- "Cannons of construction are maxims for reading and writing statues."

- unless defined, words should be interpreted in there every day meanings.

- "Ejusdem Generis:" "of the same class." For example, if the statue lists several documents relating to real property, then has a catch all at the end that says something like "and any other document" it is to be understood that this would be any other document about real property, that is, in the same class as the documents which were explicitly listed.

- Specific items take prevalence over general. If there is a conflict in rules, the more specific one would more likely to be considered to of precedence.

- Provisions enacted later (the newest ones/the most recent ones) take precedence over provisions that were enacted earlier

- "Expressio Unius:" "expressio unius est exclusio alterius" if there is a lit of items, and there isn't a specific catch all like "any other documents" only the items on the list are included.

- It should be assumed that all language is there to add something. If something could be interpreted as meaningful or completely non-meaningful, it should be considered to be meaningful. If all items in a statute are all given a penalty, the same penalty, for example, then in one part of the statute it speaks of a penalty to be had for a specific action, this penalty should be considered in addition to the blanket penalty which has already been established for all aspects of the statute. The fact that the statute states a penalty for a specific part of the statute could be considered non-meaningful since it overlaps with what has already been established, but this is not the norm in which should be used to interpret statute. Or, just because the there are variable rate charges on your taxi cab fare, it does not mean that the fixed rate charge is no long there.

- "In Pari Materia:" "of the same matter" if there is more than one statute on the same topic they should be considered together. A manifestation of this is that if a word is defined in one and not the other, there may in fact be a definition for both as a result.

- interpretation of criminal laws should be done narrowly

- using persuasive opinions from other jurisdictions is more likely to occur if the relevant law in the persuasive jurisdiction is modelled from a common source as the relevant law where the decision is being made. Based on my memory, this could happen for instance with PIPEDA and related law as PIPEDA serves as a model law which the provinces themselves are supposed to eventually implement.

- commentary is just that, it is not law, it is not absolutely authoritative but it can help in furthering your understanding of the law

- always check that lower court decisions have not changed on appeal

- was the case you are investigating later used/referenced as precedent setting?

- Recording your bad search methods van be handy in making sure that you don't repeat your past failed attempts

- commentary should be used to supplement your legal understanding not supplant it.

- deductive reasoning: apply elements of law to a real case.

- reasoning by example: compare facts of a case yet to be resolved to a similar case which has been resolved

- the rest of this chapter pertains to deductive reasoning

- use legal rules to predict the outcome of cases

- align case facts with legal rule requirements

- sometimes assumptions will be required to make a legal analysis. Since assumptions are not certain, it may be beneficial to consider the outcomes based on various assumptions

- a chart can be used in helping analyse of the facts of the case you are analysing relates to the law. A sample of this could look like this.

| element | case facts | element met? | |

| IF | List the legal elements required | list how the elements relate to the facts of the case | has it been met? |

| THEN | list the legal consequences | list how it relates to the case |

- if elements of a legal rule are not met in a case being analysed it sometimes can be useful to restate the legal rules in their negative IF THEN form.

- IF 1 and 2 would become IF not 1 or 2

- IF 1 or 2 would become IF not 1 and 2

- the same transformation would happen with the THEN portion

- drawing on analogy

- distinguishing cases

- the degree to which a case can be distinguished can suggest the degree to which the result may or should differ

- two important criteria in order to be able to use a case as an example

- needs to address the same, or very similar legal rule

- facts should be similar or same, the facts relevant to the legal rule are the most important

- some similarities and differences are more important than others

- the narrowness or the generalness of the case in which you are comparing to can guide how narrow or general your interpretation should be

- intentionality incorrectly interpreting overly narrow or broad in or to find a favourable result is unlikely to be adventageous

- Venn Diagrams to show similarities and differences

- reasoning by example cannot be used alone but supplements deductive reasoning

- policy analysis

- it may be the case that deductive reasoning and reasoning by example may not be enough

- broad society goal of laws

- policy often drives law

- considers society's interests

- based on conceptions of societal good

- could be called: legislative, government, or social policy. Is NOT "public policy"

- Public policy: "... a term of art used to identify the basis on which judges can refuse to enforce contracts or conditions attached to land transfers if they are against the good of the community or contrary to established conceptions of justice and morality."

- policy is tricky and often doesn't do a very good job of representing everyone. It is often one sided.

- stakeholder analysis can be performed here

- understand policy behind law and apply it to cases, what was the goal of the law and how does it relate to the case?

- if there is more than one policy at play, is one more important than another?

- dose one outcome of the case better serve a policy more than another?

- what outcome would result in the greatest amount of policy being served?

- Reader-Centred Writing

- when writing, take into account the characteristics of the reader

- keep to relevant points

- consider how the reader will actually go through the paper, are they likely to skim?

- What does the reader already know?

- What does the reader still need to know?

- Legal writing has specific conventions

- following these are important for many reasons including maintaining professional credibility

- legal writing is formal

- should not contain first person

- for one, it gives a more objective appearance

- Function / Format of legal memo

- aka file memo, intraoffice memo, or internal memo

- good if there is more than one lawyer involved

- can contain all sorts of information, anything that needs to be communicated

- analytical memo

- records known facts

- documents research

- sets of reasoning

- predictions of resolution

- strategy

- don't forget that the memo might be referenced in the future for similar cases

- the writer is also likely to be an audience for the memo

- common memo components

- caption: recipient's name, writers name, date, subject (client's name, file number, brief description).

- Issue(s): the legal issue

- Short Answer(s): provides the writer's position on the legal issues. Provides bottom line answers.

- Facts: The client story. If the whole story is not known it may discuss the future

- Discussion: This makes up the majority of the memo. Intro, presentation of rule of law, application of rules to facts, conclusion.

- Conclusion / Recommendations

- appendices